Living in the Indian Himalayas

When I first moved to India in 2018, I spent 18 months living in the lower Himalayas on the side of a mountain. It was one of the more unforgettable experiences of my life, and my first glimpse of sustainable living in India.

I had spent three weeks travelling by car through the lower and mid Himalayas in 2017, reaching an altitude of 18,380 feet at Khardungla in the state of Ladakh. This was a side of India I never imagined; it was beyond beautiful. From then on I wanted to spend more time in the mountains.

Living in a Traditional Mountain Home

Initially when I moved to India, I stayed in Delhi with a plan to spend the winter in the Himalayas. This was before I considered what living in a place with snow, but no central heating would be like. A family I knew ran a homestay called Himalyan Orchard Huts and had a studio apartment available for rent. After a month in Delhi the dog and I moved up to Himachal Pradesh, what many Indians consider to be the most beautiful state in India.

Himalayan Orchard Huts was built in traditional Himachali style – slate roof, cow dung floors (cow dung is sanitizing), mud and stone walls – no internal passages between rooms, but covered hallways and verandahs connecting everything. The most spectacular part – it was perched on the side of a mountain with no road access. This was both awesome and horribly inconvenient.

Without a road, it was incredibly peaceful – all that could be heard were birds and the Saal River flowing in the valley below. I used to watch flocks of parakeets flying through the valley. But everything had to get up the mountain somehow. When I bought a fridge, it took 3 porters to carry it up, and my boxes of books were brought up on the backs of donkeys.

The nearest town, Chamba was 13 km away. A quick trip in for a social visit or shopping was not possible. Going to Chamba was an all day event that required planning. First there was a mountain to trek down, then I had to wait for the local Shiva bus (which supposedly ran on a timetable, but not really) to get to the outskirts of town, or if I was lucky I could get a ride in with a family member. Most of these trips involved returning after dark. Trekking up a mountain in the dark on cow paths, carrying bags of shopping and a flashlight was not something I had ever envisioned doing, but it was part of the routine there.

Leopards sometimes frequented the area (nocturnal predators). I was pretty sure they went after smaller prey, so I wasn’t worried for my own safety while trekking up in the dark, but I never let my dog out alone at night.

A Slower, Quieter Life Style

With no television, few people and limited WiFi (it could take 3 days to watch one Netflix movie), I learned to slow down, not only in my actions but in my mind. With that much solitude you have to get comfortable with your own thoughts.

I read the Indian classics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata, occasionally helped with household chores like sorting grain, spent time outside doing yoga, tried meditation, and did lots of thinking.

Watson my dog thrived on the mountain. He roamed cow paths, ran into goats, cows, donkeys, other dogs, the occasional farmer and made best friends with the guard dog at the property. This was the equivalent of doggie nirvana for him.

Once in a while the solitude became too much, and I would take the 14 hour overnight Himachal government bus to Delhi. I’d stay in Delhi for a week or so, connect with friends, explore the capital and then head back to the mountain.

A Sustainable Lifestyle

Mountain living requires a sustainable life style. The family that ran the homestay grew everything: wheat, corn, all sorts of vegetables, berries and had hundreds of fruit trees. There was a fish pond, chickens, and cows.

Butter was homemade using cream from the milk the cows produced. Yogurt was prepared every night and kept in a special cupboard to set, eggs came from the chickens. Corn and wheat were ground into flours; fruits and vegetables turned into jams and pickles. Everything got used and almost nothing went to waste. Table scraps fed the cows and chickens. There was a compost pile, and all remaining garbage was burned. There’s no garbage pick up if there isn’t a road.

Once there was a 9 day power outage and I learned to live without electricity. Luckily we used gas (or wood fire) for cooking, but it affected everything else. Nine days is a long time to suddenly have no power. It was impossible to shower without hot water since it was nearly winter, electronics could not be charged, there was no Wifi for communication, no way to read after dark except by candlelight. It was a great lesson, and it shaped my views on what is really needed.

Traditional Cooking

My studio had a kitchen and I cooked my own breakfast and lunch, but every night I ate dinner with the family.

At the homestay meals were eaten in shifts – the labourers ate first, then the household staff and kids, and finally the family. This meant eating dinner around 9 pm (typical of Indian households – many eat dinner even later), and going to bed right after. The family sat down for chai and snacks at the time I would usually have dinner in Canada. But somehow on the mountain it worked and felt natural.

Nearly everything was cooked over a traditional mud fire pit, called a chulha, which was surprisingly efficient. Several pots could be heating and cooking at the same time. In the winter the chulha kept the kitchen warm (but smoky); I often went in there to defrost my fingers and toes.

Dinners were mostly rice, chapatis, dal and vegetables. We ate together sitting on the floor on straw mats, in a semi circle around the chulha, without cutlery. Food actually tastes better when eaten with hands. The matriarch was a great cook, and she would sit by the chulha dishing up food and replenishing our plates with fresh chapatis and rice.

This being said, guests of the homestay ate in a proper dining room at a table, with cutlery. I was there long term and wanted an authentic experience, so chose to eat with the family in their traditional kitchen.

Getting Used to Spiders and Scorpions

The spiders in Himachal were completely harmless but massive – the size of my hand. They were too big to trap, so had to be scooped up with a straw broom and dropped outside. This is when I discovered how fast spiders could be (makes sense considering they have eight legs), and I had to be faster. They frequented my studio, probably coming in through the crevices around my windows, sometimes arriving in pairs. Once I found a spider in my bed which did freak me out, despite my upgraded tolerance, but usually they stuck to the walls. I also learned (the hard way) to shake my bath towel vigorously before using to it dry off after showering.

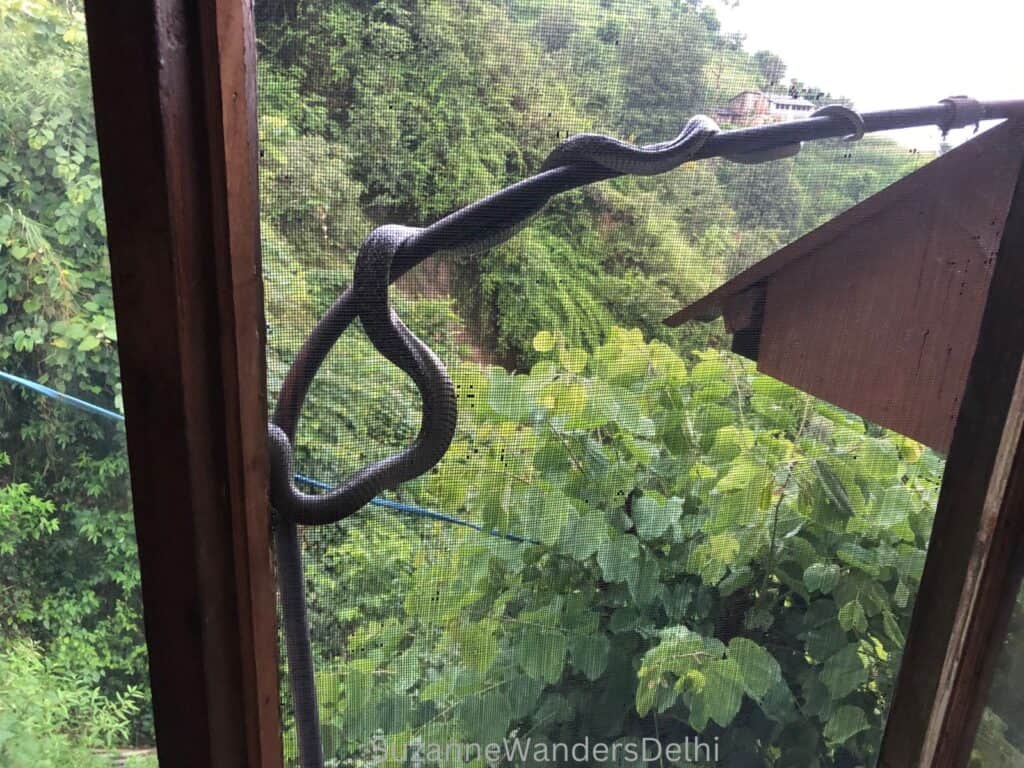

There were scorpions, but far fewer in number. The problem with scorpions is they are better camouflaged and like to hang out on floors, plus they are venomous. But the best was the snake.

One morning I woke up to see Watson glued to the window directly across from my bed, his nose pressed to the screen. A huge snake was resting along an exterior pipe and was literally nose to nose with Watson, nothing but the screen between them. It was a nonvenomous trinket snake, and eventually slithered away never to be seen again. That was my only Indian snake sighting.

Living with No Heat in Winter

Most Indians assume that Canadians are used to the cold and can tolerate an Indian winter easily. But in Canada we have central heating, which is practically non-existent in India, particularly in remote areas.

Nothing was heated in Himachal; not homes, schools, shops or businesses. The kids had their long holiday break in winter because it was too cold to sit in an unheated classroom all day. And we got snow on the mountain, it was cold. Some days I could see my breath inside my apartment.

Himachal families are used to this weather, and manage by layering up in shawls, heavy woolen sweaters and using hot water bottles in bed. I added Indian Old Monk rum to my winter survival repertoire – rum is very warming. Living without heat in winter taught me we don’t need much to manage, we’ve only been conditioned to think we do. Valuable as the lesson was, I admit I’d rather not repeat it.

Himalayan Orchard Huts

Before I moved to this guest house for 18 months, I stayed there several times as a tourist. It’s a wonderful homestay that supports sustainable tourism. If you’re considering a trip up to Himachal, I highly recommend staying here.

The location is absolutely breathtaking. There’s plenty of hiking and trekking opportunities, and a fresh water pool. Food is delicious, all home made and mostly organic. The guesthouse has its own clean mountain water source, so the water is potable. I drank it all the time and never once got sick.

I did have some unique experiences on the mountain, but some (the spiders and nine day power outage) were only because I spent such a long time there and chose to live in a local way.

It was Rough Living, Why Do It?

Well the truth is, living at the homestay in the mountains was so beautiful and peaceful it made up for all the challenges. It was a completely different lifestyle, something I needed and wanted to experience. The simple life agreed with me, and I was happy up there.

I learned it’s possible to live off the land with little reliance on anything coming in from the outside, even electricity and heat. Plus my dog had the time of his life – that was definitely the happiest he’s ever been.

The lack of a social circle and good WiFi eventually lead me back to Delhi, otherwise I probably would have stayed up there indefinitely. It’s a special place.

Don’t forget travel insurance! It’s always a good idea to carry travel insurance just in case something goes wrong. I really like and use SafetyWing